Bill Wharton is a musician whose stage name is “Sauce Boss.” Wharton uses this moniker because when he’s not playing frenetic renditions of classic Blues songs, he is hawking “Liquid Summer” (his own blend of chili sauce) and cooking enormous pots of spicy gumbo, which he then serves to his audience. It’s quite a feat to witness. More intriguing still, on his days off Wharton performs free concerts at soup kitchens, where he also serves up what he half-jokingly calls “the gospel of gumbo.”

Wharton and I first met at Terra Blues, a small, dimly-lit bar that’s a vestige of the dozens of live music clubs once operating on this stretch of Bleecker Street in Greenwich Village. Legends like Lucky Peterson, Corey Harris, and Saron Crenshaw have all played at Terra, which proudly bills itself as the only place in New York City where one can hear the Blues, 365 days a year. On the night I was present, only half of the club’s 100 or so seats were occupied, and mostly by foreign tourists. At nearby tables, I heard people speaking Japanese, Russian and Hebrew.

Wharton and I first met at Terra Blues, a small, dimly-lit bar that’s a vestige of the dozens of live music clubs once operating on this stretch of Bleecker Street in Greenwich Village. Legends like Lucky Peterson, Corey Harris, and Saron Crenshaw have all played at Terra, which proudly bills itself as the only place in New York City where one can hear the Blues, 365 days a year. On the night I was present, only half of the club’s 100 or so seats were occupied, and mostly by foreign tourists. At nearby tables, I heard people speaking Japanese, Russian and Hebrew.

I’d arranged to meet Sauce Boss backstage, where I soon learn punctuality is not high on his list of priorities. I passed the time by chatting with members of Wharton’s two-man band: Justin Headley (drums), a jiggly-bellied teddy bear of a man, with pink cheeks; and John Hart, who plays the bass guitar and holds his lank dark hair off his forehead with a neatly folded bandana. Playing with Sauce Boss, these two guys do over 100 shows a year, often staying out on the road for a month at a time. In addition, they estimate they’ve fed several hundred thousand people at homeless shelters across the United States.

I ask Hart what is the difference between a club date, and one played at a shelter.

“Actually, the vibe at soup kitchens is a lot cooler,” he claims. “It’s not like a typical Friday night crowd, where people will just show up to see whoever is playing at the club. With homeless people, we come to them, which is so unusual, they’re genuinely excited to see us.”

The Blues is a feeling more than a style of music, Headley tells me. “The songs might be about not having any money, or you’ve lost your job, your ride, your phone—maybe your wife has left you. But it’s more than that. It’s uplifting, too. Singing the Blues is how you encourage yourself when you are going through a rough patch. Our soup kitchen crowds respond to that.”

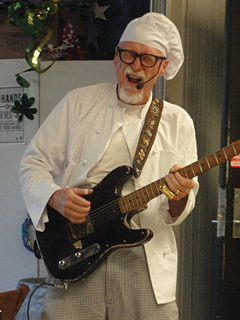

Three quarters of an hour late, and only a few minutes before he’s scheduled to go on, Wharton appears. Slope-shouldered and quite slender, he sports a white goatee beard. He’s outfitted in a chef’s uniform of a white hat, white buttoned-up jacket, and black and white checked pants—a look he’s made his own by accessorizing it with black and white “Spectator” shoes. The Sauce Boss looks a great deal like Colonel Saunders, that is, if the KFC founder had foresworn fried chicken, and gone on a serious diet.

“Singing the Blues is how you encourage yourself when you are going through a rough patch. Our soup kitchen crowds respond to that.”

Wharton seems unclear who exactly I am, even though we’d spoken several times on the telephone over the past few days, including earlier that afternoon. I’m fairly certain I smell marijuana smoke on his clothes.

Hart and Headley go off to complete a sound check of their amplifiers, while Wharton fusses with his mise en place. There are Zip-Lock bags full of ingredients for his gumbo (chopped onions, peppers, chicken stock, shrimp), gallons of filtered water, and a portable cooktop with a propane tank. Wharton also checks the contents of a black suitcase where he stores Sauce Boss compact discs, and bottles of Liquid Summer, which will be on sale after tonight’s concert. Imagining he’s in the midst of a pre-show ritual that shouldn’t be disturbed, I watch all this silently.

Suddenly, Wharton jerks his head up, and looks at me with a piercing stare. “G’head. Talk to me, brother,” he demands.

Startled, I ask him how he describes his type of Blues.

“I play a kind of bottleneck, Delta Slide,” he replies. “It’s ‘gut bucket’ Blues, and very improvisational. I think of myself as someone who just plays what I’m feeling at the time.”

He demonstrates his “bottleneck,” which is a metal tube, similar in size to the foil wrapped around an uncorked wine bottle. Worn on his left hand’s pinky, Wharton presses down on it with his third and fourth finger as he rapidly maneuvers the bottleneck up and down his guitar’s fretboard. Delta Slide, he says, began in country music and Blues, but has migrated into rock and roll bands ranging from The Doors to Metallica.

Wharton, who is 65, grew up in Orlando, Florida. Even as a child he wanted to be a musician; he started performing professionally at the age of 14. “I talked myself into a gig, and then I taught myself how to play.”

“There was a time when I was sitting in a jail on Good Friday, trying to figure out how to make a noose from a bed sheet.”

As a teenager, he was in a band called The Sapphires, which played covers of songs by Bob Dylan and The Byrds. Another band of his, The New Englanders, was a “Beatles knock off.” It wasn’t until a friend gave him an electric guitar, however, that Wharton found his way to the Blues.

“The Blues are incredibly poetic, yet they usually have the most basic lyrics,” he says. “Think of a phrase like, ‘I woke up this morning / I had two minds.’ Not ‘I woke up this morning / I felt schizophrenic,’ or ‘I woke up this morning / I was filled with existential anxiety.’ Just ‘two minds.’ It is simpler, and so much better.”

Wharton tells me about the “Rosie,” or a type of work song which was once used to enliven the rhythmic labors of slaves or prisoners. He thumps his chest with a fist, stomps his foot, and improvises a simple ditty, “Be my woman / (THUD!) / I be your man.”

“The music was their meter,” he continues. “Every time they pounded another spike in a railroad tie, or cracked another rock for a highway, the downbeat was what kept them going. That’s the thing about the Blues; they’re primal.”

“The music was their meter,” he continues. “Every time they pounded another spike in a railroad tie, or cracked another rock for a highway, the downbeat was what kept them going. That’s the thing about the Blues; they’re primal.”

As an “old white guy,” Wharton admits he’s something of a rarity in a musical genre dominated by black men. “But, I have an affinity, a true resonance with Africa,” he says. “I know what it is to suffer, too. Things haven’t always been easy for me. This is what allows me to righteously sing the Blues. I know this life.”

I ask what he means. How has he suffered?

Wharton fixes me with a hard glare. “Let me put it this way,” he begins. “There was a time when I was sitting in a jail on Good Friday, trying to figure out how to make a noose from a bed sheet.”

A stage manager appears, and asks Wharton if he’s ready to go on.

I find a seat out front, and Sauce Boss comes onstage.

“We’re gonna cook up a little food, play some Blues, and just hang out,” he says. “That O.K. with everybody?”

He opens with “Let the Big Dog Eat,” the closest thing he’s had to a hit (the director Jonathan Demme included it on the soundtrack of his 1986 film, “Something Wild.”) The lyrics are rudimentary. “Way down South / In the rain and the heat / Sure gets hot down there / Cook an egg on the concrete / Everybody on the city street says / Whoa! Let the big dog eat!”

Wharton’s music is fast, real toe-tapping, hip-shaking stuff. His long riffs are both muscular and agile. While he plays, Wharton wears a surprised expression on his face, as if the melody and lyrics were spontaneously generated, not a well-rehearsed act he does hundreds of times every year.

Some of Sauce Boss’ music taps into a rich vein of ribald sexual humor that runs through the Blues. (Think of B.B. King’s love song to his own penis called “My Ding-A-Ling,” or “Ain’t Got Nobody To Grind My Coffee,” a tune Bessie Smith used to feature in her act. As he sings a naughty lyric like “Big-legged woman / I can tell what you got cookin’ / I want to stir your pot,” Wharton rolls his eyes about like a crazy person, to make sure his audience gets the double-entendre.

He plays for a solid hour before he even casts a glance at a large stock pot that’s center stage. “I’ve just been having too much fun to start cookin’,” he says, with a chuckle.

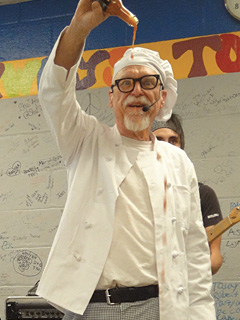

As Wharton cranks open the propane tank, and lights a flame under the pot, Headley bangs the drum set with a mighty crash that makes the whole audience jump. After adding chicken stock, onions, and peppers, Wharton pops the lid off a plastic bucket labeled, “Savoie’s Old-Fashioned Dark Roux.” He scoops up a big brown blob with a metal spoon, and shows it to the audience.

As Wharton cranks open the propane tank, and lights a flame under the pot, Headley bangs the drum set with a mighty crash that makes the whole audience jump. After adding chicken stock, onions, and peppers, Wharton pops the lid off a plastic bucket labeled, “Savoie’s Old-Fashioned Dark Roux.” He scoops up a big brown blob with a metal spoon, and shows it to the audience.

“For those of y’all that don’t know, roux is just oil and flour. Oil and flour that’s been all cooked down until it looks like this. Ain’t it gorgeous? I think roux looks like molasses! Or chocolate! Roux looks like…” Rolling his eyes in that berserk way he has, Wharton teases out the inevitable response.

“Shit!” several people scream.

Wharton’s music is fast, real toe-tapping, hip-shaking stuff. His long riffs are both muscular and agile.

“That’s right, it looks like fudge!” he counters, laughing and snorting like he’s never told this joke before. He plops the roux into the pot. As the broth for the gumbo begins to heat and thicken, Wharton takes a huge gulp from a glass of red wine. “Look around you! Turn your head left; and turn right! Everyone around you looks a little bit different, right? But celebrating our differences is what it’s all about. We can put them all in a pot, stir ‘em up, and make something that tastes really, really good. And that, my friends, is the gospel of gumbo!”

I wasn’t hungry when I’d arrived at Terra Blues, but as a seductive smell begins to float across the room, I’m ravenous. It’s well past 1:00 a.m., however, and Sauce Boss is still whaling away on his electric guitar, with no ladle in sight.

A few days later, I am in Buffalo, New York, waiting for Wharton to arrive at The Matt Urban Hope Center, a soup kitchen on Paderewski Street. I’m chatting with Tom Acara, a Sales Manager for the Conference and Event Center of Niagara Falls, whose wife, Cynthia, arranged for Sauce Boss to play a free concert here.

“This was never a rich neighborhood, but back in the day, it was extremely well-taken care of by the proud Polish people who lived here,” Acara says. He then reminds me that Ignacy Jan Paderewski was a Pole who, in the 1920’s and 30’s, was a world-renowned pianist and composer.

Buffalo is laid out on a master plan designed by Frederic Law Olmsted, Acara explains, and was the first place in America to have electric street lights, because city fathers were able to harness the hydroelectric power of nearby Niagara Falls. Bethlehem Steel once had 18,000 employees in Buffalo; General Motors, Ford, and Allied Chemicals (which made indigo blue dye for denim jeans; Levi Strauss was Allied’s biggest customer) had prospering factories here, too.

Those boom times are long gone. Paderewski Street now bisects a blighted neighborhood, with many boarded up homes, and empty store fronts. Matt Urban Hope Center typically feeds 150 people a day, though a slightly smaller crowd has shown up to see Sauce Boss who, as is his custom, is running late. Wharton is not answering his cell phone, or replying to any of her texts, and Cynthia Acara is starting to freak out.

An hour late, Sauce Boss finally saunters in. When not performing, he moves with a serene confidence there’s no need to rush.

On the contrary, his bandmates, Headly and Hart, hustle to set up their sound equipment, as well as Wharton’s cooking supplies, in front of a brightly-painted wall mural that proclaims, “PATHWAY TO PROSPERITY.”

A few minutes later, Wharton launches into “Let the Big Dog Eat.”

The energy and volume of Sauce Boss’ music soon has everyone quite riled up.

When the song ends, a man shouts, “I’m the big dog ‘round here, and I’m already eating!” He is wearing a filthy orange T-shirt that says Partner’s Pizzeria on the back. A greasy cardboard box of pizza is open on the table before him.

“O.K., big dog,” Wharton says to this guy.

He plays a few more songs for this crowd which is receptive, to say the least. In fact, the energy and volume of Sauce Boss’ music soon has everyone quite riled up. One woman is shaking her hands with an (imaginary) pair of maracas. Another guy is loudly humming along with a tuneless back-up vocal. Some people bang on their thighs, and jiggle their feet; others toss back their heads and shout. There is a lot of heckling.

“Man? You only playing two drums?” one man hollers out to Justin Headley, the percussionist. “I got me a drum set with some thirty drums in it!”

“Man? You only playing two drums?” one man hollers out to Justin Headley, the percussionist. “I got me a drum set with some thirty drums in it!”

“That sho be a raggedy-ass lookin’ guitar you got there,” someone yells, pointing an accusing finger at Wharton’s battered black Fender. (“You sho ‘nuf right there!” Wharton agrees.)

No sooner does each song end, than one woman hollers out the same question, again and again: “When you gonna start cookin’?”

Wharton appears unfazed by this commotion. “I gotta tell y’all … I like to eat! My idea of a good time is a big ‘ole bowl of gumbo, and a big ‘ole plate of biscuits, each of ‘em with a fat slice’a butter on ‘em, and drippin’ with Tupelo honey. Sound good, don’t it?”

I notice how deft Wharton is at code shifting. His audience in Greenwich Village the other night was primarily young, affluent and Caucasian, which caused him to use certain words and make certain jokes. Here in Buffalo, the crowd is older, poorer, and almost completely African-American. It’s subtle, but Wharton’s diction has become lazier for this crowd; consonants are hit softer, or disappear altogether. And, truth be told, sometimes Wharton’s patter becomes impressionistic, if not downright weird.

After he dumps an entire bottle of Liquid Summer hot sauce into the pot, he says, “We’s a gonna let it simmer down now into the primordial ooze that squishes between the toes of your taste buds.”

People are mesmerized by the gumbo’s progress. Different men and women, sometimes in groups, keep getting up and streaming forward in the middle of one of Wharton’s songs, to stare down into the bubbling fluid. In Greenwich Village, Wharton had to jump off the stage to interact with the crowd; here, the audience is joining him.

People are mesmerized by the gumbo’s progress. Different men and women, sometimes in groups, keep getting up and streaming forward in the middle of one of Wharton’s songs, to stare down into the bubbling fluid. In Greenwich Village, Wharton had to jump off the stage to interact with the crowd; here, the audience is joining him.

When it comes time to pray before the meal, Wharton does so in his own inimitable style.

“Can I get an ‘Amen?’” he yells. Unhappy with the tepid response, he again shouts “Is that all you got? Can I get an ‘Amen?’”

This time, just about everyone, myself included, shouts ‘AMEN!’”

“Well, thank you, Jesus, and thank you, Leo Fender!” Wharton cries, thereby equating the son of God with Clarence Leonidas “Leo” Fender, the son of orange grove owners in Anaheim, California, who in 1950 invented the first mass-produced electric guitar.

Cynthia and Tom Acara serve up lunch, while Wharton comes to chat with me.

How does he keep track of the timing of the gumbo, I ask; like when to add new ingredients, or when it’s done?

There are occasional mishaps, Wharton suggests. The drunk guy in Chicago who cracked a glass beer bottle into the gumbo, rendering it inedible. Or, a time in Toronto, when he was playing for a crowd of 9,000 people, and an enormous kettle slipped off its propane burner. “There was a gumbo tsunami all around the band! But these Canadian guys, they always have their snow shovels handy. They just squeegeed the whole mess off the front of the stage!”

Has cooking in soup kitchens changed him?

“Well, sure! I mean, before I was a pretty cool guy. I played a mean guitar. People wished they were me,” Wharton pauses, and cocks an eyebrow to mock what he’d just said. “But, when I started cooking in soup kitchens, it was a reality check. Life is more than collecting accolades, you know, and getting applause. Now, my main thrill is looking people straight in the eye, and giving them respect. It’s been bad out there, and it’s getting worse. Everyone has a story.”

“We’s a gonna let it simmer down now into the primordial ooze that squishes between the toes of your taste buds.”

Though I’m nervous to do so, I remind Wharton he’d mentioned a suicide attempt in prison … that bed sheet noose? I expected him to bristle, or clam up; instead he gives me a bright, big smile.

“I like to smoke pot, O.K.? So, I was growing some for myself, and maybe a little more that I’d share with friends.”

He pauses. “What happened to me was a sting. Someone pretended to be a friend of a friend, and I got busted. In some ways, I think of myself as having been a political prisoner. Someone went out of their way to set me up, and I’m still not quite sure why.”

Wharton was incarcerated for two months in 1983, and then put on three years probation. He took his time in prison as an opportunity to start up a new band. “We’d have concerts inside where all the players, and all the audience, were inmates. It was awesome!”

“And, long’s as I still got my human dignity, I can still blossom and grow!”

He then launches into a story about a guy named Calvin Craddock, who played bass guitar with him. Actually, the anecdote is about Craddock’s grandmother who grew okra in her garden in Alabama.

“Now, ‘round June, Grandma Craddock would go out to her backyard, and she’d cut herself a switch—a nice long and strong switch. Then, she’d go over to her okra plants and whip ‘em, just whip ‘em good. Well, don’t you know, come August, when she’d look at ‘em again, them okra plants would be bushing out all over, and just popping with okra! I think that’s a little like you and me, ain’t it? You can beat me up! You can whip me and try to keep me down. Maybe some parts of me will fall away, but those are my weakest bits. What’s left is my human dignity. You can’t take that away from me! And, long’s as I still got my human dignity, I can still blossom and grow!”

“Now, ‘round June, Grandma Craddock would go out to her backyard, and she’d cut herself a switch—a nice long and strong switch. Then, she’d go over to her okra plants and whip ‘em, just whip ‘em good. Well, don’t you know, come August, when she’d look at ‘em again, them okra plants would be bushing out all over, and just popping with okra! I think that’s a little like you and me, ain’t it? You can beat me up! You can whip me and try to keep me down. Maybe some parts of me will fall away, but those are my weakest bits. What’s left is my human dignity. You can’t take that away from me! And, long’s as I still got my human dignity, I can still blossom and grow!”

And that, my friends, is the gospel of gumbo.