Kyoto, Japan—Shojin Ryori is an exquisitely refined cuisine that once flourished in the many Buddhist monasteries of Kyoto, in southwestern Japan.

Shojin Ryori is macrobiotic, vegetarian, and for centuries has espoused a simple rule of healthy dining (eat seasonal, eat local) that we in the West are only recently rediscovering. Historically, the tenzo, or head chef in a Buddhist monastery, acted as a combination of psychoanalyst and dietician. Not only the priests and novitiates, or monks-in-training, but even people from the community would talk to the tenzo about their complaints—emotional, physical, and spiritual—and he’d diagnose and dispense cures in the form of food.

Shojin Ryori is macrobiotic, vegetarian, and for centuries has espoused a simple rule of healthy dining (eat seasonal, eat local) that we in the West are only recently rediscovering. Historically, the tenzo, or head chef in a Buddhist monastery, acted as a combination of psychoanalyst and dietician. Not only the priests and novitiates, or monks-in-training, but even people from the community would talk to the tenzo about their complaints—emotional, physical, and spiritual—and he’d diagnose and dispense cures in the form of food.

Intrigued to learn more about food as medicine, I discovered that finding a temple that would allow me to cook in its kitchen wasn’t easy. While there once were thousands of young men studying the tenets of Buddhism in Kyoto (if you’re interested, read The Temple of the Golden Pavilion by Yukio Mishima), current enrollment of novitiates is way down, monasteries are being turned into boutique hotels, and shojin ryori is being replaced by microwaveable noodles in styrofoam cups.

After many dead ends and leads that didn’t pan out, I was delighted when, thanks to a connection made through a friend of a friend, I suddenly began getting emails from a Kyoto priest named Giko. He wrote in a burst of short declarative sentences, kind of like typed shouts: “O.K. You come my temple. O.K. You stay four days. Then, you must leave. O.K. You cook. You learn from my wife.”

His wife? Weren’t Buddhist monks supposed to be celibate?

These questions would go unanswered for the time being. For journalists, gaining access is always something of a leap into the dark. If you press too hard for everything to be spelled out in advance, it often scares people away. Instead, I would read between the lines of Giko’s cryptic emails—“O.K. We are poor. You know we are very poor, O.K.?”—and soon enough, I had created a fully-formed Japan-tasia, with me learning all sorts of culinary cures for acne, irritable bowel syndrome, and other stress-related disorders, while I cooked alongside Giko’s wife, who I imagined as a kind of Geisha Adele Davis. The student monks would be clad in maroon robes, their heads shaved, all neatly lined up to have their rice bowls filled by Mrs. Giko and me, before they went back to their work of practicing calligraphy, or puzzling over the sutras.

“Itashimashite!” I practiced saying. This means, “you’re welcome” in Japanese.

Yes, I’d worked myself up into quite a tizzy of preconceptions by the time a Kyoto taxi driver dropped me off before a large wooden gate, plunked down in the middle of a suburban neighborhood of modest, contemporary houses. Impressive as this hand-carved, arched gate was, and two stories tall, its door was curiously low. I doubled over at the waist to enter, dragged my suitcase up a winding stone path, and past a statue of the seated Buddha. Just in case someone was watching me from inside, I made a respectful bow.

Yes, I’d worked myself up into quite a tizzy of preconceptions by the time a Kyoto taxi driver dropped me off before a large wooden gate, plunked down in the middle of a suburban neighborhood of modest, contemporary houses. Impressive as this hand-carved, arched gate was, and two stories tall, its door was curiously low. I doubled over at the waist to enter, dragged my suitcase up a winding stone path, and past a statue of the seated Buddha. Just in case someone was watching me from inside, I made a respectful bow.

Mrs. Giko answers the door. Her name is Hiromi. She is gorgeous, an elegant woman of 50, with thick black hair that pulled back into a loose French Twist. She has full, pouty lips, and pale, smooth skin. She’s slight of frame, but stacked—a chic cashmere cardigan and a pearl necklace draw my eyes to her breasts. Her voice is high and soft; it’s almost as if she’s singing a lullaby when she talks. I instantly have a crush on Hiromi. I can’t decide if I want to protect her, kiss her, or become her.

My passion is slightly cooled by one little problem. Hiromi doesn’t speak English. At her elbow stands a girlfriend of hers, Takago, who will be Hiromi’s translator and our constant companion. Takago has a saucy, sarcastic manner; she seems game for anything. She has a way of punctuating her sentences with a wink. I didn’t know people did that anymore. Wink. No matter. I like Takago instantly, too.

Before I enter the house, Takago tells me to take off my shoes. After having already spent a week traveling in Japan, I knew this custom, and impatient to comply I kick off my boots, and they thud to the floor. Hiromi whispers something to Takago, who informs me that there is no cause for such noise-making. I must slip my shoes off silently—especially when Giko-san is around—and line them up neatly next to the door.

Giko and Hiromi are the caretakers whose selfless devotion is keeping this temple—a treasure of 15th century architecture—from being turned into a sushi restaurant.

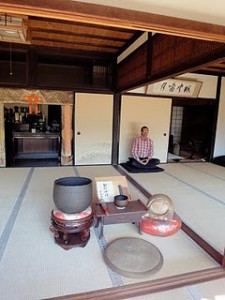

I’m slightly bugged by Takago’s reproach, but mostly I know she is right, and I am embarrassed to be such a clod. Hoping to make up for this faux-pas, I quickly perpetuate another, when I haul out my gifts. I’d brought a very fine bottle of sake from Niigata, and from Takayama, candies made from green tea. Ah, but this is a temple, not a house. Takago grabs my elbow, and pulls me after Hiromi, as we scuttle down a dark hall, and enter the main meditation hall, or zendo, a large room where floors are covered in tatami mats and the back wall is made of sliding doors that overlook a garden. Hiromi arranges my gifts on an altar in front of a gilded statue of Buddha. She lights an incense stick, some candles, and Takago, she and I all bow for what seemed an excessive amount of time. My gifts remain on the altar all week, and every morning, when Giko and I go there to meditate at 4:00 a.m., they are first and last things I see. I grow quite weary of looking at them. Was that, I wonder, the point?

Now then…where are the monks, you might be asking?

There are none.

It turns out this is a sub-temple of the bigger, and busier Ryoanji temple a few blocks away. If you have ever seen a travel magazine’s story about Kyoto, it has doubtless included a photograph of Ryoanji’s famous rock and sand garden. There used to be a constellation of 22 sub-temples encircling Ryoanji, each with their own priests, tenzo and monks-in-training. Over time, though, most of the other sub-temples have been de-sacralized, or they’ve burned down (fire is a constant fear in Kyoto, as almost all temples are built solely of wood.) Now, Ryoanji has only two sub-temples.

Giko and Hiromi are the caretakers whose selfless devotion is keeping this temple—a treasure of 15th century architecture—from being turned into a sushi restaurant.

Giko and Hiromi are the caretakers whose selfless devotion is keeping this temple—a treasure of 15th century architecture—from being turned into a sushi restaurant.

Theirs is a life of much prayer, much sacrifice, and not a whole lot of perks other than the shojin ryori food that Hiromi cooks for them. I’m not even sure they collect a salary, as Giko teaches sociology at the University of Osaka, and has to take a train two hours each way, four days a week. He was celibate until age 50, when he met and fell in love with Hiromi. She’d never married either, and was 45 when they wed.

As we drank tea together on this first afternoon, Hiromi explained all this to me. Takago would translate her friend’s words, but sometimes added her own commentary through a occasional side-of-mouth whisper or cocked eyebrow. I got the impression she was a little afraid of Giko-san, and I began to become nervous about his imminent arrival. Takago admitted she doesn’t know how to cook and is unfamiliar with the names of most vegetables, even in English. With the help of a Japanese-English dictionary, I would look up words, point them out to Takago, who’d speak to Hiromi. It sounds cumbersome and, believe me, it was. Yet, somehow the clumsiness of communication loosened things up, and soon enough the three of us were merrily peeling taro root, frying tofu, and shredding daikon radish.

Originally, shojin ryori came about as part of the Buddhist ideal of detachment from worldly possessions. The monks would go out each morning with a bowl, into which passersby would drop their donations—a prototype of the Baptist’s offering plate, I decide.

“In winter, body get cold,” Hiromi said, as Takago translated. “To warm up, it is good to eat warm foods like root vegetables—daikon, potatoes, carrots, and turnips. In the summer time, it reverse. Cucumber and tomatoes, make body cold.”

Originally, shojin ryori came about as part of the Buddhist ideal of detachment from worldly possessions. The monks would go out each morning with a bowl, into which passersby would drop their donations—a prototype of the Baptist’s offering plate, I decide. This alms gathering, known as takuhatsu, usually resulted in the monks getting different vegetables and rice, which they’d bring back to the temple, and give to the tenzo. Plain, though not exactly bland, temple food was designed to not unduly agitate or stimulate the digestive system; during prolonged periods of meditation, a monk would not suddenly be burping up onion, garlic, or spicy red peppers from lunch. Hiromi’s father is a rice farmer in Japan’s Shimane prefecture. Naturally, she knows a lot about rice, and shows me how important it is to wash it several times before cooking, or the kernels will stick together. I learn how to make a simple soup stock by boiling dried seaweed and dehydrated fish. Let me pause for a moment to say that I’ve subsequently done this back in New York and—aside from having to go to an Asian supermarket to find ingredients—nothing could be easier, cheaper, or more tasty.

I grew up in a house where we were made to “clean our plates” at each meal—meaning, eat everything we were served. Under Hiromi’s tutelage, however, this phrase takes on new meaning. She demonstrates how I am to wash my own dishes, at the table, by swirling green tea around in my rice bowl to dislodge those two or three uneaten kernels, then pour the fluid into my dish of radish (lifting up the fragments here, too), bowl to bowl, until I have a swill in which all left-over bits float. This, I am to quaff as an after-dinner drink. “Nothing go to waste,” Hiromi said.

That first day, Hiromi, Takago and I are cooking and gabbing away, we have hit our multi-lingual stride, when suddenly Hiromi’s face falls.

Takago gasps, “Giko-san is home!”

Takago gasps, “Giko-san is home!”

Substitute “Godzilla” in that last sentence, and you have a better sense of their panic. Several minutes pass, and the tension builds as we don’t hear a sound. How do they even know he’s here? I decide it’s probably best for me to stop breathing.

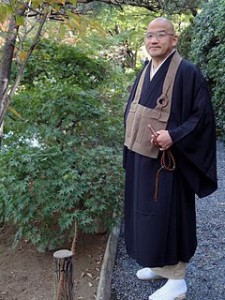

As he lumbers into the kitchen, he leads with a scowl. Giko-san turns his sour gaze to his wife, then Takago, then me; he didn’t seem particularly pleased to see any of us. He is short, with a squat, blocky build, like a Sumo wrestler who’s gone on a crash diet. He has a shaved head, and fleshy, protuberant ears. His nose is shaped like an Isosceles triangle, small at the bridge, but swelling forth into a thick base, with two nearly fuming nostrils that are extinguished by a wispy black mustache.

Even I have trouble believing what happened next.

Takago had prepped me for this fraught moment, by providing a little script in Japanese, which I had laboriously written out in my notebook in block capitols. I’d done my best to set it to memory, but upon Giko’s arrival, I got rattled, and it was nowhere to be found inside my head. I began rifling the pages of my notebook, until I found the words, which I read slowly aloud. KONBONWA! HAJIMEMASHITE STEPHEN DES. OSEWANI NARIMASU!

Takago told me this meant something like, “Good evening, master. I am your humble guest, Stephen. Please take care of me.” It was, I inferred, a Buddhist way of saying, “You could kill me right now, if you wanted to, but wouldn’t it be nice if you didn’t?” Earlier that afternoon, I wasn’t sure why Takago was convinced I needed to learn this phrase, but now I understood. When I finished, the barest flicker of a smile crossed Giko-san’s face. Then, he went off to meditate.

Hiromi gave me a look that said, “He’s really a kitten.”

Takago gave me a wink that said, “What a freak!”

It was going to be a long week.

At dinner that night, Giko still seemed grumpy and was anxious to correct my table manners. Shojin Ryori, I discovered, involves a rather elaborate dining etiquette. While eating, I had to sit on my legs, knees out before me, back perfectly straight. There was much adjustment until I managed to hold my chopsticks to Giko’s satisfaction. No food from one bowl could touch another—until, that is, the “washing up” ritual, as described earlier. My rice dish always had to be placed to the left of the miso soup, and oopsie-daisy, if I ever happened to rest my elbows on the table, all hell broke lose. My own father ran a pretty strict table. When I was about 9 or 10, I recall him once reaching across and giving my thumb a whack with his knife, as he was disgusted with my gross habit of manually shoving food onto a fork. Dad was a softie in comparison to Giko-san, however. It was as if all the lessons he’d stored up to teach his (phantom) noviates, would now be drummed into me.

At dinner that night, Giko still seemed grumpy and was anxious to correct my table manners. Shojin Ryori, I discovered, involves a rather elaborate dining etiquette. While eating, I had to sit on my legs, knees out before me, back perfectly straight. There was much adjustment until I managed to hold my chopsticks to Giko’s satisfaction. No food from one bowl could touch another—until, that is, the “washing up” ritual, as described earlier. My rice dish always had to be placed to the left of the miso soup, and oopsie-daisy, if I ever happened to rest my elbows on the table, all hell broke lose. My own father ran a pretty strict table. When I was about 9 or 10, I recall him once reaching across and giving my thumb a whack with his knife, as he was disgusted with my gross habit of manually shoving food onto a fork. Dad was a softie in comparison to Giko-san, however. It was as if all the lessons he’d stored up to teach his (phantom) noviates, would now be drummed into me.

Gradually, though, Giko-san’s mood began to improve. Maybe this is partially explained by the knee-touching intimacy of eating at a squat piece of furniture called a kotasu. It’s kind of a cross between a coffee table and a tea cozy. Hiromi set out the food—“Our poor supper,” Giko apologized. “We are poor.”—on top of the kotasu, and then we all quickly jostled to sit on the floor, get our legs underneath it, and cover them with heated blankets that drape down from the table’s four sides. Most Japanese houses do not have a furnace, and make do with a few strategically placed electric heaters, and the kotasu. Here we huddled, lower body toasty-warm, upper torso freezing, while Giko-san held forth on various topics. He, to my great relief, did speak English. His sense of humor was so bone-dry, though, I wasn’t fully convinced he was trying to be funny. Still, I ended up laughing a lot at what Giko was saying, and he took no offense.

Like me, Giko-san is a preacher’s kid. He was the second son of a priest in Kyoto. His brother is also a priest and oversees a temple that is bigger and more well-endowed. Giko did a stint at the Yokoji Mountain Zen Center in Los Angeles, and likes to complain about American egotism. “People in your country suffer from a very keen me-ism, a nearly incurable me-ism. I am the best! I am smart! I am pretty! Me, me, me! I found it very embarrassing.”

Tibetan Buddhism is popular in the United States, he believes, partially because of the Dalai Lama’s charisma, but mostly “due to that American actor…” Giko-san twisted the strands of his mustache as he tried to remember. I really, really didn’t want to be the one who had to say it. “Richard Gere,” I eventually whispered. “That’s right,” Giko-san boomed. “RICHARD GERE!” He then frowned at me, as if by speaking the dreaded name, I admitted that I am yet another stupid American who has chosen to be a Buddhist only because this religion has a celebrity tie-in.

After this bumpy beginning, however, we settled into a most satisfactory routine. Up at 4:00 a.m. every day, I would meditate with Giko. Buddhists speak of the “monkey mind,” as a way of describing how difficult it can be to relax our consciousness. The secret of meditating? Don’t try too hard, Giko advised. Lightly close the eyes, gaze upon the back of your forehead, and drift. When distracting thought arise, watch them, but don’t stare at them, he said. They are twigs on a stream. They’ll pass. A good mantra to repeat? “Let it go.”

After this bumpy beginning, however, we settled into a most satisfactory routine. Up at 4:00 a.m. every day, I would meditate with Giko. Buddhists speak of the “monkey mind,” as a way of describing how difficult it can be to relax our consciousness. The secret of meditating? Don’t try too hard, Giko advised. Lightly close the eyes, gaze upon the back of your forehead, and drift. When distracting thought arise, watch them, but don’t stare at them, he said. They are twigs on a stream. They’ll pass. A good mantra to repeat? “Let it go.”

Then, during our breakfasts, tucked under the kotasu, I would grill Giko-san before he got on his train to Osaka. This is my preferred way of conversing, of course. I ask clever questions; you supply quotable answers. It took Giko no time, however, to catch me in my own game. Then, he refused to play.

Buddhism is often especially difficult for Christians to understand, he contends, because it (Buddhism) is not a belief system, there are no “rules,” and no definitive answers. The Judeo-Christian ethos is based on tradition, on received wisdom, and honors a kind of “blind faith,” that is not affected by anything we observe on an everyday basis. Buddhism is, in every way, the opposite. Buddhism rejects dogma, and insists the only way to enlightenment is through empirical experience. “Don’t believe anything that anyone tells you, including me,” Giko said. “No one is holier than you are.” He told me of a Zen master, Len Chi, who went so far as to proclaim, “If you meet the Buddha, kill the Buddha!” Meaning, don’t unquestioningly do what anyone tells you to do, no matter how enlightened they may seem—even the Buddha.

Let’s see. Giko was cautioning me not to follow any one else’s advice. But wasn’t that a piece of advice? This was a perfectly circular conundrum, the sort of head-scratcher that Buddhists call a koan.

Confusing things further for me, was Hiromi. At first, she’d appeared meek. I quickly discovered she was a woman of steely will and firm convictions. Hiromi had a belief system, rules, and definitive answers—not about Buddhism, per se, but about food, style, and design. Suddenly, I was the monk-in-training she’d never had, too, and Hiromi wanted me to learn her lessons, just as badly as Giko wanted me to “unlearn” his.

Hiromi, Takago and I spent hours in Nishiki Market, Kyoto’s open-air food street. It’s only six block long, but crammed with hundreds of shops (some of them only a few feet wide), that sell everything from eggplants the size of my thumb, to cabbage heads shaped like watermelons. We sampled dozens of varieties of tofu, and countless types of apples. Hiromi would ask the sellers to slice their fruit in half, horizontally, to show off the distinctive pattern the apple’s seed pod makes at its center—sometimes a spindly star, or a fat square, or an amorphous belly button. One morning, we searched for hours to find the perfect sesame seed roaster—a delicate mesh contraption that you can whisk through flames to gently brown the small sesame seeds. It is, to my mind, a tool of somewhat limited use (like garden tweezers), but Hiromi was convinced I needed one.

Hiromi, Takago and I spent hours in Nishiki Market, Kyoto’s open-air food street. It’s only six block long, but crammed with hundreds of shops (some of them only a few feet wide), that sell everything from eggplants the size of my thumb, to cabbage heads shaped like watermelons. We sampled dozens of varieties of tofu, and countless types of apples. Hiromi would ask the sellers to slice their fruit in half, horizontally, to show off the distinctive pattern the apple’s seed pod makes at its center—sometimes a spindly star, or a fat square, or an amorphous belly button. One morning, we searched for hours to find the perfect sesame seed roaster—a delicate mesh contraption that you can whisk through flames to gently brown the small sesame seeds. It is, to my mind, a tool of somewhat limited use (like garden tweezers), but Hiromi was convinced I needed one.

At the end of my visit, Osaka University was on holiday, and Giko off work for the afternoon. He surprised me with a plan that we go meet some of his priest friends at other temples in Kyoto. We ended up at Daitojo-ji, founded in 1326, which is where Giko-san himself trained as a novitiate. Since the 16th century, this temple has cultivated monks who are masters of a tea ceremony—one of which Giko arranges for us to attend. Before we go in, he points to a stone-rimmed basin of water, with a ladle, where the monks wash their hands and mouths before prayers. There were four Japanese characters carved here in a circle, and Giko-san told me they signified the words, “I” “Only” “Understand” “Sufficient.” Though they were placed at the noon, three, six, and nine o’clock positions on a time piece, these words could be randomly shuffled, he noted, with no loss of meaning. “Only I understand sufficient.” “Understand, only I sufficient.” “Sufficient, I only understand.” And so on.

It’s not good or bad, sacred or secular, Heaven or Hell. O.K.? It all just is. Be here now.

“But what does it mean?” My question, as I heard it in my ears, was nearly a whine.

“It means,” he said, mimicking my urgent tone, “we are each of us alone. We can only satisfy ourselves. And that is enough. Do not be eager for more.”

We went into the tea ceremony. This was no simple affair of plopping a bag into hot water. Instead, we are treated to a spectacle of jade-green powdered tea placed in bowls, and whipped into a fragrant froth, like a tea frappe. The tea itself is called gyokuro (“jewel dew”—don’t you love it?), and is the result of tea bushes being covered for several weeks before harvest. Lack of direct sunlight is believed to make tea leaves sweeter-tasting, as does their being picked only by hand. We were sitting, Giko, his priest friend, and I, in a diminutive pagoda, overlooking a manicured interior garden. I was dizzy with delight over how beautiful everything was, and I wished I could understand how Giko’s philosophy could be merged with Hiromi’s. What was, I silently wondered, a Buddhist understanding of aesthetics? Was beauty a pathway to the divine?”

Instead, I surprised myself by asking something altogether different. “Giko-san, do you believe there is life after death?”

“I have no idea,” Giko immediately replied. “Who knows? No one knows! O.K.? It is a stupid question, really. In Japanese, there is a word, ‘muki.’ It means, something that is unimportant, something not worth thinking about. Your question is muki!” He then laughed, waving his hand in front of his nose, as if I’d farted, and he was trying to mitigate the odor.

Wow. I must be the dullest student he’s ever had. It’s clear that Giko-san is, by now, quite out of patience with me.

Wow. I must be the dullest student he’s ever had. It’s clear that Giko-san is, by now, quite out of patience with me.

“How do you live, at this moment?,” he continued. “That is the only thing that’s important! Eating, praying, meditating, shitting, fucking—they are the same thing. All are holy. All should be taken equally seriously. It’s not good or bad, sacred or secular, Heaven or Hell. O.K.? It all just is. Be here now.”

Giko is shouting, and the delicate rice paper walls of the dollhouse we’re drinking tea in are quivering, like a tympanum that’s just been given a strong pounding.