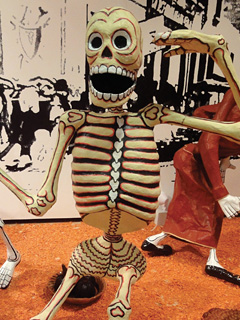

You’ve seen pictures of her, I’m sure. She’s a dignified, older woman who always has on a broad-brimmed hat that’s decorated with silk flowers and ostrich feathers. She wears a floor-length dress, and carries a parasol to shield her skin from the sun.

Actually, come to think of it, this lady has no skin. She’s a living, breathing skeleton called La Calavera Catrina.

Christmas has Santa Claus; Easter, the bunny. Down Mexico way, when in late October everyone celebrates El Dia de Los Muertos (Day of the Dead), La Catrina is mascot for families and friends who gather to celebrate memories of those who have died. She was my constant companion when I traveled to Guadalajara, Mexico, to cook a Day of the Dead dinner for a group of homeless street kids, and transgendered sex workers.

Christmas has Santa Claus; Easter, the bunny. Down Mexico way, when in late October everyone celebrates El Dia de Los Muertos (Day of the Dead), La Catrina is mascot for families and friends who gather to celebrate memories of those who have died. She was my constant companion when I traveled to Guadalajara, Mexico, to cook a Day of the Dead dinner for a group of homeless street kids, and transgendered sex workers.

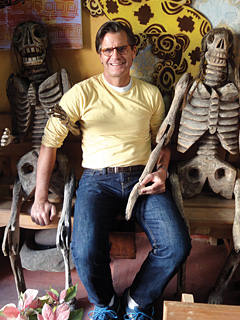

This came about when a mutual friend put me in touch with Rev. David Kalke, who is a bishop in something called the Ecumenical Catholic Church. The E.C.C. has nothing whatsoever to do with the Vatican, or the Pope. In fact, Kalke’s work often pits him directly against the Roman Catholic church which, in Guadalajara at least, tends to more diligently address needs of wealthy and powerful people, rather than the poor. Relentless, at times exhausting, in his advocacy for the underprivileged, Kalke is one of the bravest and most progressively political people I’ve ever had the opportunity to meet. He may drive a smuggled red Mini-Cooper car and have a peculiar weakness for hoary old jokes, but Rev. David Kalke is a saint.

He’s also no fool. When we talked on the phone a month or so before I traveled down Guadalajara, Kalke told me he was delighted to help me arrange una fiesta, but he wanted me to be realistic about the difficulties we might face in getting a crowd to show up. “I work with a community of outcasts,” he explained. “These kids are not used to anyone doing anything nice for them, much less arranging a party in their honor. I’m sure many of them will be suspicious of what we’re doing. They may even imagine it is some sort of trick by the police. I don’t think we have to be too terribly concerned about violence, but it’s always good to be cautious. I’m willing to take the risk, if you are. Why don’t you think it over, and call me back?”

“These kids are not used to anyone doing anything nice for them. They may even imagine it is some sort of trick by the police.”

I puzzled this over. Not surprisingly, I was terribly concerned about what Kalke said we didn’t need to be terribly concerned about. But, I decided if he was game, I was, too.

Guadalajara is the second largest city in Mexico, and has a population of eight million people—about the same as New York City’s. Capitol of the state of Jalisco, this region was settled by Spaniards in the 1540’s, or only a few decades after Hernán Cortés first conquered Moctezuma, the Aztec emperor. What would eventually be called Guadalajara was an area found to be extremely rich in both silver and gold. It also had a robust water supply; surprising, as it is surrounded by desert. (The name Guadalajara derives from an Arabic word that means “water from rocks.”) Tequila is the main source of income for Jalisco today.

As we drove into town from the airport, Kalke told me about the first time he conducted a eucharist ceremony in Guadalajara. Shortly before that morning’s services were to begin, he was dismayed to discover there was no communion wine. He instructed an old man who was the church’s caretaker to hurry off to the market and buy some “vino.” Unfortunately, Kalke was unaware that in the local dialect of Spanish, “vino” can mean wine, but is more typically used to mean tequila. He was already standing at the altar, when the caretaker brought him a chalice brimming with potent juice from the blue agave plant. Nervous, flustered, and unwilling to turn the eucharist into “Margaritaville,” Kalke made a stupid decision to down the entire chalice in one sip, while ordering the caretaker to go find some vino tinto.

“I don’t remember much of the service after that,” he says, with a sly grin.

Kalke grew up on a farm in rural Iowa. He must come from tough stock; his mother is 101, and still healthy. After college, he spent several years in Chile, which was then roiled by the bloody aftermath of a United States-backed coup in 1973, which deposed President Salvador Allende. “There were human rights violations going on in Chile that no one has ever heard of,” Kalke says.

He came back to America, and tried to raise awareness of the dire political situation in Chile by going on a cross-country speaking tour, under the auspices of the International Association Against Torture. As a result of this work, he began to think about liberation theology. He attended both Union Theological Seminary in New York City, and the Hamma School of Theology, an institution for the training of Lutheran ministers, in Canton, Ohio. After graduating from Hamma, Kalke focussed on work with refugees and solidarity efforts, spending a great deal of his time traveling in Central and South America.

I get the impression he enjoyed being a thorn in the side of his bourgeoise congregants more than they enjoyed being poked.

When I ask his definition of “liberation theology,” Kalke considers the question for a moment before he replies, “You are involved in a political process and this reflects on your actions, theologically. You are in the streets, working with people who’ve been kidnapped, battered, or ‘disappeared.’ You’re not sitting in your office, smoking a pipe, and writing books about ‘The Historical Jesus.’”

Kalke clearly relishes being in the streets. I also get the impression he enjoyed being a thorn in the side of his bourgeoise congregants more than they enjoyed being poked. Recounting his decades of parish ministry, Kalke acknowledges his activism tended to wear out his welcome with congregations. His career ended in San Bernadino, California where, true to form, he was fired for focusing too much of his energies on building a community center to minister to gang members.

Kalke clearly relishes being in the streets. I also get the impression he enjoyed being a thorn in the side of his bourgeoise congregants more than they enjoyed being poked. Recounting his decades of parish ministry, Kalke acknowledges his activism tended to wear out his welcome with congregations. His career ended in San Bernadino, California where, true to form, he was fired for focusing too much of his energies on building a community center to minister to gang members.

He moved to Guadalajara in 2009, ostensibly to retire. Soon enough, though, he’d started a social service agency called Comunidad de los Martines (The Community of the Martins—named for St. Martin of Tours, Martin Luther, St. Martin of Porres, and Martin Luther King, Jr.)

By now, we’ve arrived in downtown Guadalajara. Kalke takes me to see Plaza Tapatia, a multi-tiered park, with fountains and covered arcades, which is directly behind the imposingly grand Catholic Cathedral. Plaza Tapatia is hub to most of the city’s sex trade. As we walk about, Kalke explains there are an estimated 3,000 female prostitutes in Guadalajara, and 500 transgendered sex workers (or individuals who were born male, but identify and dress as women.)

Many of their customers are older, white, American men who’ve come to Mexico to retire, or have traveled here as sex tourists.

“I suppose I could have been one of them,” Kalke says.

Seeing how blatantly these assignations are arranged—there are many chubby gringos talking to slim-hipped young girls and boys—is startling. The cost of living in Mexico is cheap, but it’s outrageous how little these prostitutes are paid for intimate acts. Oral sex earns anywhere between 50 to 100 pesos ($4 to $8 U.S. dollars), while the fee for vaginal or anal sex “soars” up to somewhere around 250 pesos ($20 U.S. dollars). Transgendered prostitutes, I’m surprised to learn, get paid more than do “real” women.

One of Kalke’s goals is to unionize the sex workers, as they are in Argentina and Holland. Some might question if this is a worthwhile effort for a priest; nothing seems to make Kalke happier, though, than to challenge conventional thinking.

After our brief tour of central Guadalajara, Kalke drives us about twenty minutes away to Polanco, the part of town where he lives. Polanco is a poor district, settled maybe 45 years ago by squatters who simply laid claim to the land. Most of his neighbors do not have title to their property or houses.

Kalke opened a coffee shop here, Cafe Los Martines, which operates as a “safe space” for local kids, where they can hang out and be shielded from gangs, or other dangerous temptations. There is a rack with sexual literature and a box, always in need of refilling, where he gives away free condoms. At the cafe, I meet Carla and Yvonne, two young women who Kalke says will assist me for the next couple days. (I also was accompanied on this trip by two pals from New York—Mark Ledzian and Katie Daley—and I’d arranged to bring down my niece, Amy, as well as Mia, a friend of her’s from San Francisco.) Carla is a student in culinary school; Yvonne is a single mother. Neither speaks any English or, if they do, they’re too shy to attempt its usage. My Spanish will be given quite a work-out.

Kalke opened a coffee shop here, Cafe Los Martines, which operates as a “safe space” for local kids, where they can hang out and be shielded from gangs, or other dangerous temptations. There is a rack with sexual literature and a box, always in need of refilling, where he gives away free condoms. At the cafe, I meet Carla and Yvonne, two young women who Kalke says will assist me for the next couple days. (I also was accompanied on this trip by two pals from New York—Mark Ledzian and Katie Daley—and I’d arranged to bring down my niece, Amy, as well as Mia, a friend of her’s from San Francisco.) Carla is a student in culinary school; Yvonne is a single mother. Neither speaks any English or, if they do, they’re too shy to attempt its usage. My Spanish will be given quite a work-out.

The cafe’s kitchen has a small oven, with only one rack inside; two of its four burners on the cooktop are not functional. Kalke has brought a four-cup food processor from his own kitchen, as well as a couple of lasagna pans. I am disheartened by the prospect of cooking enough food for 150 people with this equipment, but do my best to hide my fears.

There is a rack with sexual literature and a box, always in need of refilling, where he gives away free condoms.

“Is everything what you expected?” Kalke asks.

“No, it’s better!” I boldly lie. “This will be terrific!”

The next two days race by. Shopping in the markets, in Spanish, while trying to convert things from pounds and cups into the metric system is my first challenge. (I have to keep repeating to myself, “1 kilo equals 2.2 pounds.”) Kalke, in his well-meaning way, frustrates my plans at nearly every turn.

To save time, for instance, he’d “pre-ordered” a lot of things based on a tentative menu we’d discussed a few weeks earlier. I’d specifically asked him not to shop for me, as every chef, if at all possible, wants to choose the ingredients they’re going to cook. Now, I am horrified to see how much he’s bought. There are monstrous mesh bags holding at least 50 onions, each the size of a grapefruit; dozens of heads of garlic; bunches of cilantro that resemble shrubbery; and woven baskets spilling over with tomatoes, avocados and tomatillos. Not to mention, clear plastic bags full of chicken, pork and beef that are so heavy, I can barely lift them. By my hurried calculations (“1 kilo equals …”) there is almost a pound of protein for each guest who will attend. Then, there’s rice, salad and apple cobbler.

Kalke refuses to hear me. Poor people in Guadalajara eat very simply, he says, and are accustomed to having little more for dinner each night than a glass of milk, and a piece of bread. If this is going to be a fiesta, we need to really give these folks something to enjoy! “Everything will get eaten, Stephen,” he says. “What’s not consumed at the party will either go to a school for the blind, or to my neighbors, who’ve never seen a feast like you are going to make!” I want to believe him, but I am certain this is way too much food, and it is going to take an incredible amount of work to prepare it in a tiny kitchen, with two burners at my disposal.

Thank you, Amy, Mia, Katie and Mark—oh yes, and Carla and Yvonne, tambien!

We all worked like demons. Jet lag, knife wounds, steamy temperatures, buzzing flies, upset stomachs—nothing could stop us. I felt a little unhinged at times, my mood swinging from euphoria (“these meatballs are incredibly delicious!”) to dark and all-consuming despair (“this goddamn fucking oven!”)

We all worked like demons. Jet lag, knife wounds, steamy temperatures, buzzing flies, upset stomachs—nothing could stop us. I felt a little unhinged at times, my mood swinging from euphoria (“these meatballs are incredibly delicious!”) to dark and all-consuming despair (“this goddamn fucking oven!”)

Late on the first afternoon, Kalke showed up again with Pedro Chavez, who is his primary contact with Guadalajara’s sex workers. Chavez is 35-years-old, quite tall, and amply built, if going slightly soft at his waist. He is training to be a lawyer, but also owns a small mortuary and funeral home in Compostela, which is a flyspeck of a village about an hour and half bus ride outside of Guadalajara.

“We’ve had trans get murdered, and they’re from out of state. Their families, even if we are able to get in contact with them, refuse to come claim the body,” he says.

Chavez suggests we head over to Doña Diabla, a gay bar downtown where our party will take place on the following evening.

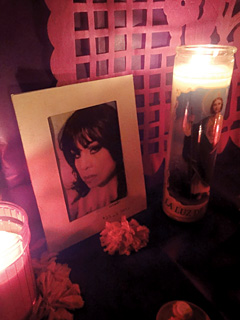

Inside the bar, I see billboard-sized photographs of María Félix. She was Mexico’s biggest movie star in the 1940’s; “Doña Diabla” (Madam Devil) is her best-known and best-loved film. Along one wall is a painted mural where a variety of large hands are shown waving, holding cigarettes, or making the peace symbol. Several of the fingers have their flesh eaten away, with bare bones showing through. This death in life theme is also evident on an altar that’s been set up near the bar’s entrance, on which are placed memento mori such as candles, flowers, and skulls made from sugar candy, as well as photographs of several transgendered sex workers who died, or were killed, in the past few years.

Inside the bar, I see billboard-sized photographs of María Félix. She was Mexico’s biggest movie star in the 1940’s; “Doña Diabla” (Madam Devil) is her best-known and best-loved film. Along one wall is a painted mural where a variety of large hands are shown waving, holding cigarettes, or making the peace symbol. Several of the fingers have their flesh eaten away, with bare bones showing through. This death in life theme is also evident on an altar that’s been set up near the bar’s entrance, on which are placed memento mori such as candles, flowers, and skulls made from sugar candy, as well as photographs of several transgendered sex workers who died, or were killed, in the past few years.

As Kalke and I look at this together, he says, “Pedro was concerned I would disapprove of having figures of the devil on a Day of the Dead altar.” He then shakes his head, incredulously. “I would think, by now, Pedro would know I’m no fan of doctrinal purity.”

Chavez offers to take me on a tour of neighborhoods in Guadalajara, other than Plaza Tapatia, where transgendered prostitutes (Chavez refers to them, simply, as “trans”) ply their trade. He knows of at least thirty different locales around town, including storefronts that appear to be hair salons, but are actually brothels.

He hails a taxi, and as we ride, Chavez tells me clients sometimes become enraged when they discover they’ve ended up with something different than a “real” woman. “We’ve had trans get murdered, and they’re from out of state. Their families, even if we are able to get in contact with them, refuse to come claim the body,” he says.

Later, Kalke tells me that in several of these sad cases, Chavez has arranged for a prostitute’s funeral and burial, at his own expense, from his Compostela funeral home.

You might think it improbable a client could be this clueless about what he is purchasing. However, here’s a couple facts to keep in mind. First, the client is often drunk. Very drunk. Mexico’s is a culture, like Japan’s, where excessive consumption of alcohol is seen as a proof of masculinity, but where the ability to “hold your liquor” is not all that important. (An old joke has it that men in the U.S. will drink until they fall; Mexican men drink until they crawl.) Secondly, Mexican women tend to wear a lot of make-up. One routinely sees cashiers or waitresses who are wearing three shades of eyeshadow, heavy mascara, false eyelashes, and thick lipstick. As such, the heavily made-up trans do not look all that different from other women.

We eventually end up at the Posada San Juan, a hotel where rooms on the upper floors can be had for what a posted sign declared the “Happy Time Rate” of 150 pesos for three hours ($12 U.S. dollars), though rooms are also rented for considerably shorter amounts of time. Twenty minutes, say, or even ten. Chavez wants me to know this is a “respectable sex hotel, not some trashy place,” which is why he keeps a small office here, from where he distributes free condoms and lubricant, as well as literature about safe sex, and AIDS transmission. He also conducts “rapid” HIV tests; of several hundred given during the month of September in this office, Chavez told me 7% of the individuals tested HIV positive.

We eventually end up at the Posada San Juan, a hotel where rooms on the upper floors can be had for what a posted sign declared the “Happy Time Rate” of 150 pesos for three hours ($12 U.S. dollars), though rooms are also rented for considerably shorter amounts of time. Twenty minutes, say, or even ten. Chavez wants me to know this is a “respectable sex hotel, not some trashy place,” which is why he keeps a small office here, from where he distributes free condoms and lubricant, as well as literature about safe sex, and AIDS transmission. He also conducts “rapid” HIV tests; of several hundred given during the month of September in this office, Chavez told me 7% of the individuals tested HIV positive.

As we chat, girls drift in and out of Chavez’ office to say hello, or to grab condoms. Blessed with the compassion (and patience) of a high school guidance counselor, Chavez remembers key facts about each—what state they come from, how old they are, how long ago they got breast implants—so they feel noticed and cared for. It is chilly outside (maybe 55 degrees Farenheit), but most of the girls are dressed in low-cut blouses to highlight their cleavage, and skirts so short, you can see the lower half of their buttocks. They teeter about on high-heeled shoes.

Maybelline, who is 20, tells Chavez about spending a night in jail. Jasmine is wearing a bright fuschia shade of lipstick; when she smiles, I see braces on her teeth. I’m guessing she is 17. At 37, Fanny has a slightly tougher attitude, and is dressed like she’s just stepped off the beach at Acapulco. Fanny has on a turquoise sweater, a white mini-skirt, and a pair of platform sandals with a wedged heel made from coiled rope.

Men in the U.S. will drink until they fall; Mexican men drink until they crawl.

On the whole, I am impressed with how attractive these girls are. If I saw one of them on the subway in New York, I would not know they were transgendered. When I ask Chavez if most have had an operation to surgically remove their penises, he appears shocked.

“No! Why would they? That is their money maker!”

I’d mistakenly assumed these prostitutes were the passive sexual partner. Pedro explains, however, that up to 80 percent of men who hire a trans want to be anally penetrated. A lot of these clients are Roman Catholic, married, and deeply homophobic. The idea of having sex with a man is repellent to them; being fucked by a woman is not.

I ask what is the average age most of the girls start, and how long can they do this work?

“Trans usually begin at about age 15, and by the time they are 22 or 23, many of them have gotten fat.” Pedro gives his own belly an affectionate rub. “People don’t pay for fat!”

The following morning, Amy, Mia, Katie, Mark, and I were back in the cafe kitchen, working for a second day. We cooked until 5:30 p.m., when we loaded up Kalke’s van to take all the food over to Doña Diabla.

Since we were last there, the nightclub has been transformed. There are many tables set up with vases full of marigolds, the traditional flower for Day of the Dead parties. There are the votive candles I insisted we needed, and papel picado, or Mexican cut-paper streamers, which hang from the ceiling. Everything looked great; I was thrilled.

I tried to put on a brave face, but I was sad and disappointed. It was hard not to feel the last two days had been wasted effort.

Only problem was, at 8:30 p.m., when the party was supposed to begin, there were, at most, 10 people present. At 9:00 p.m, maybe 15. At 9:45 p.m., 30.

The evening is a disaster. Pedro kept moaning that he had a “confirmed” list of 150 guests who were “definitely” coming. Yeah, right. And I’m Pancho Villa.

It’s not like Kalke hadn’t warned me. He’s been upfront from the very beginning about the challenges we were facing in throwing a party for people who life had not treated too well.

I tried to put on a brave face, but I was sad and disappointed. It was hard not to feel the last two days had been wasted effort.

That’s when I saw a group of 10 or 12 young men, who I decided looked suspiciously rough and tough. Several are wearing baseball caps with the John Deere tractor logo on them. They are skinny, and their jeans are dirty and frayed. I can’t quite figure out what they are doing at this dinner. To me, they look like the sort of kid who’s itching for trouble, who might pick a fight, and then beat up a gay, or transgendered, person. Oh great! On top of everything else, now we are going to have the violence Kalke wasn’t terribly concerned about.

I rushed off to find him, and asked Kalke what was going on these guys.

“They are farm boys, who’ve grown up poor, most of them way out in the countryside,” he explained. “Often, they are the eldest son, and their parents say to them, you need to go to Guadalajara, make some money, and send it home to help us out. These young men find themselves in the center of a city with as many people as New York. They are poor, uneducated, and without any job skills. They’re living on the street and hungry. When they run out of money, the only thing they have left to sell is their bodies.”

Hearing this, my impressions changed instantly. No. This can’t be. These boys are babies; some of them look like they are barely fourteen years old! I’d judged them as troublemakers, only to realize the trouble was in my mind. I made a decision, right then and there. Even if this is all who showed up, I’d do everything I could to make sure these 30 people—and these farm boys—would have a night to remember.

Despite the late hour, Kalke and Chavez were keeping their hopes alive. Neither wanted to serve the food until more people arrived. Instead, we’d let the show begin.

The show! This had been another sore point for me. When Kalke told me our fiesta was going to feature performances by three different drag queens, and each was going to do a set of five songs, I was worried this was too lengthy an entertainment. Though I raised my concerns repeatedly, Kalke always swatted them away.

I’d expected the drag queens to be lip-syncing to Lady Gaga or Katy Perry. However, Mexico has its own pantheon of pop divas, like Gloria Trevi, Belinda, and Thalia; it’s their music which was recycled into camp humor. The first singer was especially wild. Dressed all in leather, with boots that had six inch heels, she raced about the club tirelessly, and at one point hopped up on the bar, threading her way through all the beer bottles and shot glasses of tequila littered there. While she sang, more and more people kept appearing. I now understood those present were calling friends on their cell phones, telling them the party was fun, and they should get themselves over to Doña Diabla.

I’d expected the drag queens to be lip-syncing to Lady Gaga or Katy Perry. However, Mexico has its own pantheon of pop divas, like Gloria Trevi, Belinda, and Thalia; it’s their music which was recycled into camp humor. The first singer was especially wild. Dressed all in leather, with boots that had six inch heels, she raced about the club tirelessly, and at one point hopped up on the bar, threading her way through all the beer bottles and shot glasses of tequila littered there. While she sang, more and more people kept appearing. I now understood those present were calling friends on their cell phones, telling them the party was fun, and they should get themselves over to Doña Diabla.

When the show was finally over around 10:30 p.m., the crowd had tripled in size, to maybe 125. Nearly every seat in the bar was now full; Chavez and Kalke determine it’s time to eat.

Amy, Mia, Katie and I were all positioned behind a buffet table. In front of us were the mountains of food we’d cooked. Kalke said a short prayer, and the word “amen” was like a gun being fired before a marathon run. Guests came charging at us from all directions! There was no protocol about lining up in a queue, or any order whatsoever. It was complete bedlam. We frantically scooped up chicken, meatballs, pork, rice and salad, as plates were shoved at us from every angle and all directions. Buen Provecho, I kept saying, over and over. People were eating like they’d never seen food before. Only after everyone had been helped to at least two plates each, did the chaos begin to subside. Only then did I allow myself to exhale.

People are circulating between tables; everyone is laughing and flirting. Over by the wall, I see one table has been taken over by a large group of trans, all sitting together. There’s maybe 40 girls, if not more. They are being watched over by Giovanni, a guy who I’d seen the evening before, working as the night clerk at the Posada San Juan, which is the “respectable” sex hotel where Pedro Chavez has his office. Giovanni is seated at one end of the table, and from what I observe of his demeanor, he is acting as if he’s a combination of Daddy Warbucks and Professor Henry Higgins. He’s gesturing to one girl to put a napkin in her lap while she eats; to another, to lower her voice a bit. The girls seem to want his attention, to please him, and gain his favor. I thought it was all very sweet, really.

People are circulating between tables; everyone is laughing and flirting. Over by the wall, I see one table has been taken over by a large group of trans, all sitting together. There’s maybe 40 girls, if not more. They are being watched over by Giovanni, a guy who I’d seen the evening before, working as the night clerk at the Posada San Juan, which is the “respectable” sex hotel where Pedro Chavez has his office. Giovanni is seated at one end of the table, and from what I observe of his demeanor, he is acting as if he’s a combination of Daddy Warbucks and Professor Henry Higgins. He’s gesturing to one girl to put a napkin in her lap while she eats; to another, to lower her voice a bit. The girls seem to want his attention, to please him, and gain his favor. I thought it was all very sweet, really.

When I point this out to Kalke, once more he tells me appearances can be deceiving. “I’m not sure sometimes if Giovanni is a good shepherd to his flock, or if he’s running a brothel, and acting as their pimp.” He then looked at me, and laughed. “But, if it all made sense, we wouldn’t call it the underworld, right?”

The party went on well past midnight, with still more guests arriving. Though I’d forgotten all about it, Amy and Mia were vigilant enough to put out the apple cobbler, and squirt generous dollops of whipped cream on each serving. Even after all the food we’d already dished out, they seemed to be doing a good business getting rid of the dessert.

At some point, in the early morning hours, there was a special “award” ceremony, in which Kalke asked all five of us Americans to step forward to receive special recognition. It is exactly the sort of moment I’d begged him to spare us. I’d wanted our actions to be anonymous, I said, and instead we were being handed certificates with gold foil stickers and ribbons, as well as gifts. Mine is a figurine of La Calavera Catrina; about sixteen inches high, and made out of metal. She’s a bony and ugly old hag, but it’s love at first sight.

At some point, in the early morning hours, there was a special “award” ceremony, in which Kalke asked all five of us Americans to step forward to receive special recognition. It is exactly the sort of moment I’d begged him to spare us. I’d wanted our actions to be anonymous, I said, and instead we were being handed certificates with gold foil stickers and ribbons, as well as gifts. Mine is a figurine of La Calavera Catrina; about sixteen inches high, and made out of metal. She’s a bony and ugly old hag, but it’s love at first sight.

I’m still clutching this skeleton doll in my hand, when a DJ amped up the music, and a couple of the trans pulled me into their circle on the dance floor. I boogied for a while with Fanny, and then with Jasmine. In the room’s flashing lights, her braces were glittering like sparklers. I look up at one point to see Rev. David Kalke smiling at me. He makes a two thumbs-up sign.

It was the Day of the Dead, and I was happy to be alive.